‘The Lady Doth Protest…’: Mapping Feminist Movements, Moments and Mobilisations

FWSA Biennial Conference

University of Nottingham

June 21st-23rd 2013

Playing on Shakespeare’s oft-(mis)quoted idiom, ‘The Lady Doth Protest’, the FWSA’s biennial conference welcomed a varied and international audience to the University of Nottingham for a three-day conference from the 21st-23rd June 2013. With the theme ‘Mapping Feminist Movements, Moments and Mobilisations,’ this conference aimed to analyse the history of feminism on the global stage to its continuing significance in times of austerity and international political unrest. ‘The Lady Doth Protest’ functioned as a truly interdisciplinary space to discuss feminism within the academy and in activist movements, featuring three keynotes from leading activist-scholars, an advocacy and activism roundtable headed by by The Feminist Library, AWAVA and WLUML, and a three-day interactive exhibition from Music & Liberation: Women’s Liberation Music Making in the UK, 1970-1989. If this wasn’t enough, the organisers also arranged evening entertainment with the raucous Lashings of Ginger Beer Time, a Queer Feminist Burlesque Collective who will be performing at The Fringe this year, and a film screening of Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years, a poignant documentary directed by Dagmar Schultz. It is a feat in itself to review the sheer breadth of activities on offer so in an attempt to be brief I will focus on the keynote addresses and the panels I attended. To hear more on the entertainment, exhibition and activist sentiments of the conference, I direct you to Donna Marie Alexander’s review here.

At first glance the four-parallel panel programme looks impressive, if a little overwhelming. Across the weekend the diversity of papers was clear. From panels on negotiating neoliberalism to spirituality and feminism, ‘The Lady Doth Protest’ interrogated feminist pedagogies, critical ontologies and the practical exploration of ‘new’ feminist questions. With such a rich programme one might feel in danger of missing out on all the conference had to offer, however, the organisers thought of this too. For the benefit of attendees and non-attendees alike the organisers arranged bloggers and live-tweeters to be stationed across all panels, and at routine points these summaries were uploaded onto the FWSA conference website.

Championing each day the FWSA arranged a keynote address from an established activist-scholar. Introducing day one, Dr Nirmal Puwar (Goldsmiths, University of London) explored the act of space invading in feminist history. Warning against problematic romanticising Pumar nevertheless delighted the audience with tales of Emmeline Pankhurst’s suffragette ju jitsu bodyguards, Marion Wallace-Dunlop’s subversive stencil graffiti, and the House of Commons protest in 1908. However, Pumar primarily focused on the use of sound as a protest device, citing Pussy Riot’s ‘Punk Prayer’ to Judith Butler’s Who sings the nation-state? During this address Pumar aired the affective video art performance ‘Turbulent’ by Shirin Neshat which explores the variety of ways women can take up space in the name of protest. In this video Iranian vocalist and composer Sussan Deyhim transgresses spatial and social boundaries through singing, an act prohibited for women in Iran:

The second day was brought firmly into the present with Professor Nadje Al-Ali’s (SOAS, University of London) keynote address on protest, mobilisation and change in the Middle East and the ‘Arab Spring.’ Al-Ali discussed the contributions and marginalisation of feminist and women’s groups in times of wider political change, referencing Egypt’s Tahrir Square demonstration on International Women’s Day 2011 in which two-hundred women were outnumbered, unprotected by the military, and denied freedom of speech. Asking the difficult question ‘is democracy bad for women?’ Al-Ali shed light on the intricacies of democratic systems when there is national unrest, asserting that election without due process and education frequently leads to institutionalised secularism. Consequently, this makes it difficult for feminist and women’s groups to operate independently from the dominant powers. In the question session afterwards, the audience reflected on the all-too-common separation of ‘citizen’ and ‘woman’ in times of national unrest: ‘We are not here as women, we are here as citizens.’

On the third day Professor Diane Elson (Emeritus Professor, University of Essex) shifted the focus to the UK and the current impact of austerity measures on women and children. Chair of the UK Women’s Budget Group (WBG) Professor Elson presented WBG’s economic analysis and revealed the disproportionate effects of austerity for women and single-parent families. I was reminded that if some of the information was not new, this is due to the work of the UK WBG and the Fawcett Society in bringing this information to the attention of the government and journalists. In a worrying development, Elson revealed how the Universal Credit change will push a return to sole male breadwinner households.

As for the panels I attended, these were focused on literature and engaged with the politics of the page. Presenters discussed iconic pop-feminist texts from Greer to Moran, post/feminist representations in the fiction of Michele Roberts and the rape/revenge film, and the destabilising function of Judith Halberstam’s “queer art of failure” in trans fiction. Other presenters looked beyond the fiction page and located moments of feminism in South Asian autobiography, while others problematised the gender-equalizing resolution 1325 in the United Nations and its revival of Hegel’s ‘beautiful soul.’ Engaging, thought-provoking and well-presented, I left the conference with actor Will Rogers’s words in my ears: ‘A man only learns in two ways, one by reading and the other by association with smarter people.’

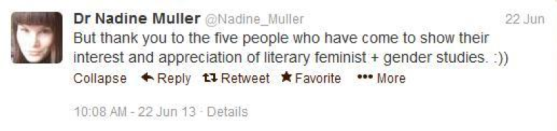

Yet still, the literature panels were sparsely attended in relation to other panels focused on the social sciences and activism. There are positives and negatives to arranging panels by discipline and both were felt. ‘The New Academic’ Nadine Muller, presenting at the event, accurately summed up some of the drawbacks:

For me as an early postgraduate researcher not presenting at the conference, a smaller audience has its advantages. Smaller audiences make it is easier to approach other attendees and it can often transform stuffy question sessions into more fluid conversations. At the close of the conference it was the questions raised in these panel discussions that stuck with me. How can we define women’s writing when many women writers reproduce the same patterns of marginalization? Does writing have to rely on didactics to be defined as feminist? Why do we do what we do – what is the political potential of literature?

When we turn our gaze to these questions that remain at the forefront of our minds as scholars and feminists we are reminded of the importance of feminist conferences as critical forums that challenge us; before the lady doth protest, the lady doth question. The FWSA’s 2013 biennial conference excelled as an intersectional feminist space that presented not only important emerging research but important difficulties, new and old, within feminist activism and the academy.

A shorter version of this review was posted on the PG CWWN website on the 31/07/2013.